Introduction

Coaches, teachers, preceptors, trainers, shepherds, directors, and others, through observing and listening, through example, questions, demonstration, and advice, may offer to others ways of mastering skills within a brief or extended relationship. As we use the term here, mentorship employs such processes to enhance those seeking or practicing licensed or ordained service to God in ministering to God’s people and the world.

A highly skilled person may not have the natural ability to transmit a particular skill to others. Sometimes a less-skilled person will prove to be a better mentor if this person can assist the mentee in developing necessary skills and wisdom. For example, a fantastic swim coach may not be the greatest swimmer. A successful mentor is not someone with a particular title or role, but someone with a level of skill sufficient to introduce and train someone else, and the ability to inspire the development of skills.

A mentor/mentee relationship is a partnership. Thus, a mentee must desire such a partnership with the aim of developing the identified skills and be open to receiving shared wisdom.

These Guidelines aim to point toward, and support, useful mentor/mentee relationships by which both may benefit. Many of the points below are obvious but may be worth reviewing. Please contribute your ideas for future versions of this document.

What Is — and Isn’t — Mentoring

Mentoring is…

- Mentoring is about developing specific skills — with the values, principles, resources, and practice leading to justified confidence and success.

- Mentoring is more like a partnership than a tutor-student relationship. It is a “coming alongside” a peer, and/or colleague and offering observation and shared wisdom.

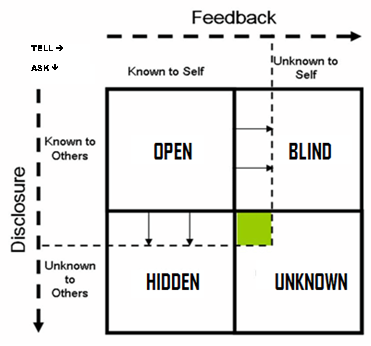

Mentoring is for both the novice and the high-performer; anyone, at any skill level, can benefit from mentoring. Even the most acclaimed opera singer may retain a mentor to point out things of which the singer may not be fully aware. The “Jo-Hari Window” illustrates the possibility of gaining greater knowledge of oneself exercising a skill through honest and trust-worthy reflection and feedback from another.

Mentoring is not…

- Mentoring is not counseling.

- Mentoring is not about fixing or restoring someone.

- Its purpose is not therapeutic.

- It should not encourage dependence.

How to Mentor

Your faithfulness in mentoring may help you discover new things about yourself and your craft, and further enhance it, with the joy of contributing to another’s growth in God’s kingdom.

1. Relish God’s love. — As appropriate, remind yourself and your mentee of God’s presence within — and the gift of offering service. Affirming what works and building on even small accomplishments may be more faithful than beginning with, or focusing on, what seems defective or wrong with the effort. A forthright assessment of a glaring performance failure can always be placed in the context of God’s love of the person — speaking the truth in love.

2. Observe, listen well, and ask questions. — Different styles of listening may be appropriate at different times. Some styles are appreciative, empathetic, comprehensive, discerning, and evaluative. While the mentor’s own specific skills may lead naturally to questions as the mentee develops his or her own skills, questions such as these may be sometimes useful:

- What was the mentee’s intent with this activity?

- How does it arise within the mentee’s life of the spirit?

- What resources did the mentee find available and useful?

- What was the process by which the activity was planned?

- What challenges did the mentee discover?

- What does the mentee want to ask you?

- What does the mentee not ask?

- Encourage and assist the mentee to identify solutions to challenges and to explore opportunities rather than lay answers on a platter for the mentee to accept or reject.

3. Provide language. — Reflect to the mentee what you have observed and heard to celebrate, reassure, and measure the effectiveness of your mentee’s activity. Give your mentee information of which the mentee was unaware, and place this in a larger context (your knowledge not only of skills but also about situations, organizations, and circumstances). The language we use often clarifies our understanding of reality. Rephrasing the mentee’s words — perhaps in technical theological vocabulary, perhaps in secularizing it — may enlarge an understanding of the thought or activity under consideration. Eliciting or offering distinctions may be helpful — here are three paired examples: (1) balance or juggle, (2) care or worry, and (3) excellence or perfection.

Concerning excellence or perfection, the Rev. Dr. David E. Nelson writes says that perfection is a dead-end street. No matter how hard one’s work and how well one performs, a perfectionist still feels inadequate. “I should have done better.” Instead, a person driven by excellence does one’s best in the given time and situation, and learns from both successes and disappointments, ending with a sense of satisfaction and a vision to excel even further in the future.

4. Discover adjustments. — Part of nurturing the mentee may be to imagine alternate situations for the activity exhibiting the skill being developed. How would the activity be affected by a different time, place, those involved, emotional affect, or alternate approaches by the mentee? It might be useful for you to demonstrate the activity under consideration or to role-play. How would the mentee adjust the activity given what has been exchanged so far in the conversation? How would the activity be different if the mentee has just now gained deeper understanding of oneself?

5. Offer endorsements. — Genuine words praise for the mentee’s work, the mentee’s questions, and the mentee’s advancement in the skill(s) being developed may be placed in the context of God’s embrace

and as part of our service to God and to others. (At some point an endorsement the form of informal or formal public or ecclesiastical recognition may be appropriate.)

6. Summarize the session. — At the end of each session, ask the mentee if the mentee is getting the help desired and how you might be even more helpful. Ask the mentee to summarize what has been learned and gained and offer your own summary as well. Your conclusion may well include “What I want for you is . . . .” (It is seldom useful to use the more frequent expression, “What I want from you is …”)

7. Identify the next step.— You and the mentee may identify and articulate the next step in mastering the skills being developed, a step small or large. It may be some form of review — or it may be studying new material — or practicing a new activity — or adding someone to the conversation for a specific purpose. At any rate, if possible, schedule the forthcoming session with clear expectations for yourself and the mentee.

How to be Mentored

1. Honor your mentor. — In many cases, while the Diocese may offer suggestions based on many factors of availability, you will be the one to select your mentor. You and your mentor want to be comfortable with each other. Your mentor is giving time and the benefit of skill and experience to you. It goes without saying you want to respect such a gift to your own development.

2. Preview the process. — Review the section above, How to Mentor, and, with each point, consider how you can gain the most from the mentoring relationship.

3. Success. — If formal recognition — certificate, license, or ordination — is expected to celebrate your success, offer your mentor whatever evidence is required for your fulfillment of the process.

Additional Resources

- Listening Hearts

- www.internalchange.com

- www.communicationtheory.org/the-johari-window-model/

- www.cres.org/pubs/appreciativeinquiry.htm

Updates

- 07-11-2022. Original version uploaded to website